On Styles and Syntheses: Thoughts Inspired by the Work and the Works of Paul Cezanne

by Howard Gardner

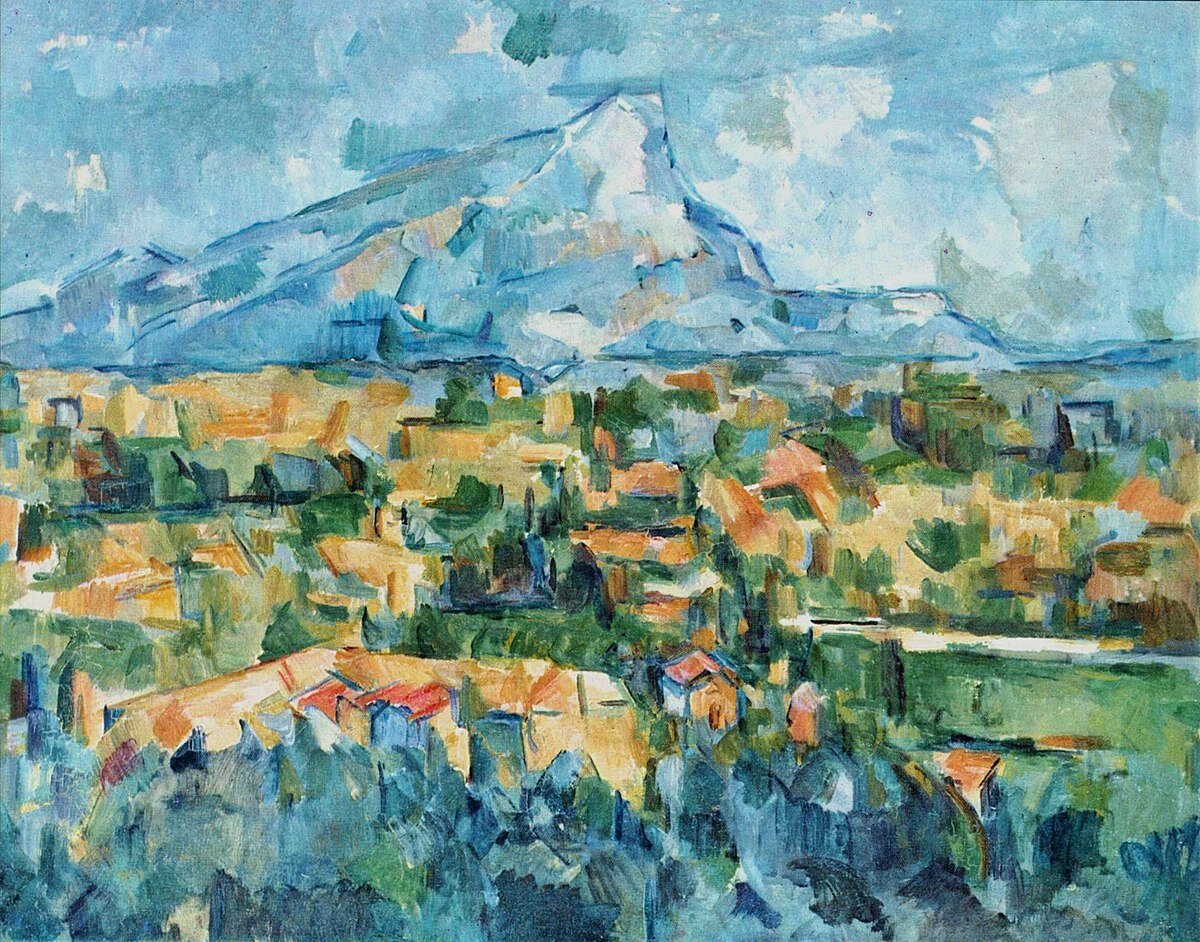

Mont-Sainte Victoire series (1904)

The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei (DVD-ROM), distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH. ISBN: 3936122202.

Suppose I posed the following question to a group of relatively well-informed persons: “Which visual artist in Europe, working toward the end of the 19th century, was virtually unknown at the time of his death but is now greatly valued?”

I can predict the overwhelming response—it would be “Vincent van Gogh”. As portrayed in many books and films, van Gogh sold no works in his lifetime; he presumptively committed suicide; but now his canvases sell for tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars.

Let’s say I were to reword the question slightly: “Which artist in Europe, working toward the end of the 19th century, was virtually unknown at the time of his death, but is now widely recognized as having had the greatest influence on subsequent Western painting?” In this case, the correct answer might be surprising—it’s Paul Cezanne.

Indeed, there is virtually complete consensus among artists, critics, historians that this is the case.

Consider the witnesses: Henri Matisse: “the father of us all”; Pablo Picasso: “the mother who protects her children;” contemporary art critic Jed Perl: “Cezanne has an outside role in nearly every account of modern art.” I could extend this list for pages.

In the recent history of Western visual art, Cezanne is seen as far more important than others of his contemporaries: not just van Gogh, but also Paul Gaugin, Eduard Manet, Claude Monet, Georges Seurat, Pierre Renoir, Paul Gaugin, Eduard Manet—even Camille Pissarro (with whom Cezanne worked closely for a decade and whose paintings from the 1870s are sometimes difficult to distinguish from those of Cezanne).

Why is Cezanne so valorized?

Let me offer a brief account. I will then argue that the ‘case of Cezanne’ provides valuable perspectives on broader issues of artistic styles and of scholarly syntheses.

With the rise of photography, many viewers of paintings and drawing no longer looked to artists to give a photographically faithful version of persons, nature, the physical world. Accordingly, various artists sought to highlight other facets—Manet’s bold subject matter and shallow space; Monet’s depiction of light and water; Seurat’s pointillism, Gaugin’s brightly colored flat backgrounds in exotic settings, to name a few. Initially, in the 1870s these iconoclastic artists were rejected by the traditional “Salon des Beaux Arts.” Retaliating pointedly with their “Salon des Refusés,” they eventually gained audiences, sold works for significant amounts, were recognized, and valorized in the artistic press.

Cezanne was no less ambitious, no less eager to make a mark; and having a secure income from his affluent family, he was able to proceed as he wished. More than his contemporaries, Cezanne peered beyond the ostensible subjects of his portraits and pastoral scenes to foreground the underlying structures and patterns—so much so that his landscapes and portraits came increasingly to resemble geometric infrastructures, outlines, even architectural sketches, if you will.

Indeed, we now appreciate that—intentionally or not—Cezanne was laying the groundwork for the next major period of European fine visual arts. Of course, that was cubism, where the ostensible subject matter was unimportant, indeed, often deliberately profane; what was important was the play among geometric forms—hinted at in Picasso’s epochal les demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), laid out explicitly in analytic cubism (1908-1912) and then climaxed in (appropriately named) synthetic cubism (1913-1915).

Which in turn laid the groundwork for abstract expressionism, then pop art, then hyper realism: the saga continues, happily in not entirely predictable ways.

Let me shift gears.

Note the terms that I just mentioned: Even if you lack familiarity with the history of Western painting in the last 150 years, you will probably recognize the names, labels, characterizations of different styles—whether it’s early, middle, or late Cezanne; cubism, neo-classicism, abstract expressionism, pop art, op art etc.

Which brings me, at last, to the stated topic of this blog.

Whether we are cognizant of it or not, whether we are acting deliberately or not, each of us has a style (or, possibly, more than one style), and this is particularly true of artists.

In this respect, the founders of cubism offer an instructive contrast. In the case of Picasso, his Cubist style was but one of many that he, a versatile magician, exhibited over the course of his long and prolific life. In contrast, his close comrade in artistic arms, Georges Braque, who lived nearly as long, had just one mature style, that of the Cubist artist. (We might say something similar about Juan Gris, Fernand Leger, and other cubist artists of lesser renown.)

But while artists clearly have their own styles, they may not be fully aware of their style as they work. It is in retrospect when artists and art historians look back over a body of work that a coherent style connecting their works is recognized. Recognizing a style, and conferring a phrase on it, represents an attempt to classify similarities (and differences) in ways that make sense to viewers, audiences, students, fellow citizens.

ASIDE: I might announce that I am writing in the style of Howard Gardner—and I might wonder whether I have any followers or imitators or caricaturists. But my desire, my announcement, is only of biographical interest. The meaningful naming and acknowledgement of styles is the province of subsequent scholars, writers, teachers, observers, students.

While artists have been at their trade for millennia, a serious effort to create categories of artistic style really emanates (at least in the West) from German humanistic scholarship in the 18-20th centuries. Going beyond the descriptions of specific artists, writers like Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768) created categories, classifications, cohorts. Sometimes these groupings were just simply descriptive—the century, the city, the school (as in ‘The School of Rembrandt’ or ‘fragments of Greek pottery of the 4th century B.C.’)

A more ambitious effort entailed the stipulation of categories of artists (neo-Classical, Romantic Impressionist, cubist, abstract expressionists and so on). Not all such labels work; not all last; but once a promising description has congealed and has made its way into texts, lectures, and exhibits, it takes on a life of its own. Even if labels such as “the Romantic poets,” “the symphonic composers of the Classical era,” or “the Impressionists” come to be regarded as grossly inadequate and overly broad, it would be very hard to obliterate these descriptors from memory or discourse or textbooks. They become the principal categories by which we think of art and artists.

Indeed, they constitute authoritative ‘syntheses of artistic styles’ or of ‘artistic style.’

My current interest in this topic emanated from a stunning exhibition of Cezanne drawings at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. I puzzled about Cezanne’s long period of obscurity, how he negotiated his life—with frequent disappointments and occasional triumphs—and why, in the years immediately following his death, he became recognized as a seminal force in art history… perhaps as important as Pablo Picasso or Andy Warhol, (both of whom, of course, are better known to the general public). I wondered which aspects of his personal biographical trek emerged as important for subsequent history—how were they recognized, described, imitated, absorbed. I wondered— how, in turn, they gave rise to a consensual narrative that Cezanne was a pivotal figure—perhaps the pivotal figure in the artistic history of the West in the last 140 years.

Only then did I recall – vividly!—that the concept “artistic style” had been a major preoccupation of mine during my student days. Right after college, I read, devoured, and outlined a (largely unknown) work by the Swiss art historian Heinrich Wölfflin (1864-1945). In his Principles of Art History, this scholar outlined five dimensions—in effect a grid—for classifying style across the visual arts for the record the dimensions: linear/painterly; plane and recession; closed and open form; multiplicity and unity; clearness and unclearness.

Just a few years later, when searching for a topic in developmental psychology for my doctoral dissertation, I determined to study when and how children become able to appreciate artistic styles. I approached this empirical question by asking children to group paintings in various ways. Of particular interest was noting when children could overlook the subject matter (e.g., a portrait by Velasquez and a portrait by Matisse). Only when they had attained that developmental milestone could children instead focus on the common features of technique, color use, arrangement, etc., which allow us to group together paintings by Velasquez, as against those by Matisse or another artist from the recent or the distant past. Subject matter turns out to be a very potent attractant; it takes a certain amount of sophistication to group together a portrait and a pastoral scene by Rembrandt, while grouping together a portrait and pastoral scene created by Van Gogh, three centuries later.

Of course, in music, we do not ordinarily have subject matter; (the closest would be the topics of a song, or the prominence of certain instruments). And yet those with a musical flair can easily group together works of the classical period, or works of the succeeding romantic period, as well as instances of 12 tone music, jazz, rock, or hip hop.

Revealingly, in most cases the categories of style do not come from the artists themselves (or even from their promoters). Rather, these categorizations are proposed by scholars or aficionados who can overlook superficial characteristics. Such individuals are prototypical synthesizers: they can group often ostensibly dissimilar works together because they can perceive the deep similarities in organization, tempo, orchestration meter which characterize one group of compositions in comparison with another, A musically oriented Wölfflin could readily come up with an appropriate set that distinguish classical from romantic scores…. indeed, we find just such contrasts in the writings of musical scholar Charles Rosen.

Those who can recognize stylistic features and create an effective classification, are master synthesizers: they are pulling together into a coherent whole disparate threads across different works by different artists. They sense what is important, defining, lasting, inclusive, independent of whether the producers themselves are aware of them. And if producers—like playwright Stoppard (blog here), or poet Emily Dickinson (blog here)—have a distinctive style, it’s immaterial whether they themselves recognize it (or even intend to create such a style). Rather, it’s important that these defining features or symptoms ‘strike’ careful students of the genre and makes sense—or come to make sense to those who are being introduced to it and need to draw upon it. It’s of biographical interest whether Cezanne recognized what was distinctive in his work and how it might influence his successors; it’s of scholarly interest how his influence spread; and it’s of interest to those of us who study ‘synthesizing’ to examine how his example may illuminate the emergence and recognition of style and styles.

References

Danchev, A. Cezanne: A life. New York: Pantheon, 2012.

Gardner, H. “Style sensitivity in children,” Human Development 1972, 15: 325-338.

Hauptman, J. and Friedman, S. Cezanne Drawing. New York: MoMA, 2021

Rewald, John. Cezanne. New York: Henry Adams, 1986

Rosen, C. The Classical Style. New York: Norton, 1972

Rosen, C. The Romantic Generation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Wolfflin. Principles of Art History. New York: Dover publications, n. d.